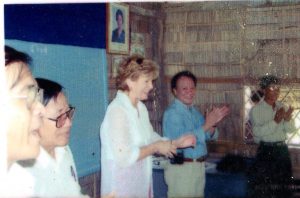

A younger Lyn with the prince and entourage.

Early in the turn of the century, I was invited to go to Cambodia by a former colleague who had been impressed by the work I was doing with Indigenous children in Queensland. At this time, he was working as an adviser to a member of the royal family and as I understood it, my job was to do some kind of feasibility study to see if the program could be useful for the children in Cambodia. I’ve always been up for a challenge so without too much hesitation, I agreed to go.

It is difficult for me to describe the feelings I experienced almost from the moment of my arrival. Driving from the airport I could already sense the dichotomies of this place. Shadows of French occupation remained in the crumbling buildings which even now portrayed the elegance and opulence that they must have worn with pride at a time long past. Now many had become squat habitations for displaced families.

That afternoon I was picked up by a stranger on a motor bike. My ‘chauffeur’ beckoned me to sit on the back and as we crossed the crazy traffic, I smiled to myself, remembering that my father had called me the previous night and begged me not to go to this dangerous country. Yet here I was at dusk, sitting behind a stranger who was navigating through a throbbing stream of traffic which seemed to move to a beat all of its own, and that certainly did not include obeying traffic rules. I was taken to the residence of Prince Sirivudh and soon came face to face with the charming prince. He and his partner were delightful hosts and were keen to hear about what I had been doing in Australia.

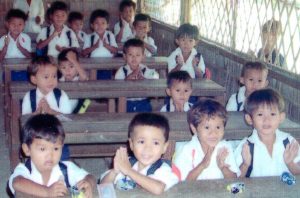

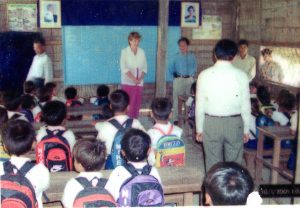

A few days later I was taken by the prince, and his guards, to see a school he had built. The prince was eager to receive feedback on this achievement. What I found was a pretty, one roomed building with a thatched roof. My heart sank as I saw the lack of any learning materials beside a chalkboard which was the only teaching aid available to the teacher. The school room was packed to the brim with thirty-five eager faces. The air of enthusiasm would have been welcome to any educator. It was obvious that these young students wanted to be here. There was an air of expectation, but what could a white, English speaking ex-educator offer these smiling young students. The notion of happiness is universal so ‘If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands,’ seemed a good place to start and before long they joined in the clapping, stamping, dancing, twirling and other movements, with much gusto and the prince and his entourage also joined in.

As we returned to Phnom Penh, I attempted to voice my concerns and as a result, an appointment was made for me to meet the minister for education. Unfortunately, he was out of town, but the assistant minister was happy to see me. I told him how I had felt about seeing the eager little faces who were expected to learn without any reading material. I expressed my feeling that these children were the hope of Cambodia’s future and that is where the emphasis should be. So much knowledge and expertise had been wiped out by the Pol Pot regime and it was vital that these children were given the education needed to get this country on its feet again. I think he found me to be rather opinionated but asked me what I thought was needed. I explained the need for graded readers in their language and preferably in their culture as there was still a French influence that appeared to pervade the attempts at education. He asked me if I would be willing to stay and write material and that is when it hit me that there really was nothing I could do. A feeling of complete helplessness threatened to overtake my usual optimistic outlook. I left Cambodia feeling I had achieved nothing and was only a little appeased when somebody sent me a Cambodian paper which included an advertisement appealing for assistance to write graded reading material for schools.

I have often reflected on my inability to help. I treasure a letter I received from the prince thanking me for my visit, but in my heart of hearts I felt I had failed. So many years later I have found an opportunity to perhaps make a difference for some children in Cambodia. This weekend I begin interviewing a wonderful young woman, Donna Cooper, who has an amazing story. She is managing to make a real difference and I feel privileged that she has asked me to write her story. Hopefully it will assist her to gain more sponsors so she can continue to provide education for disadvantaged children in Cambodia. I am so excited. More will be posted in the weeks to come.